Shadow Feeders

Shadow Feeders

A field note by Maelin of the Low Reach, apprentice to the catalogues of Aldric the Woodwise

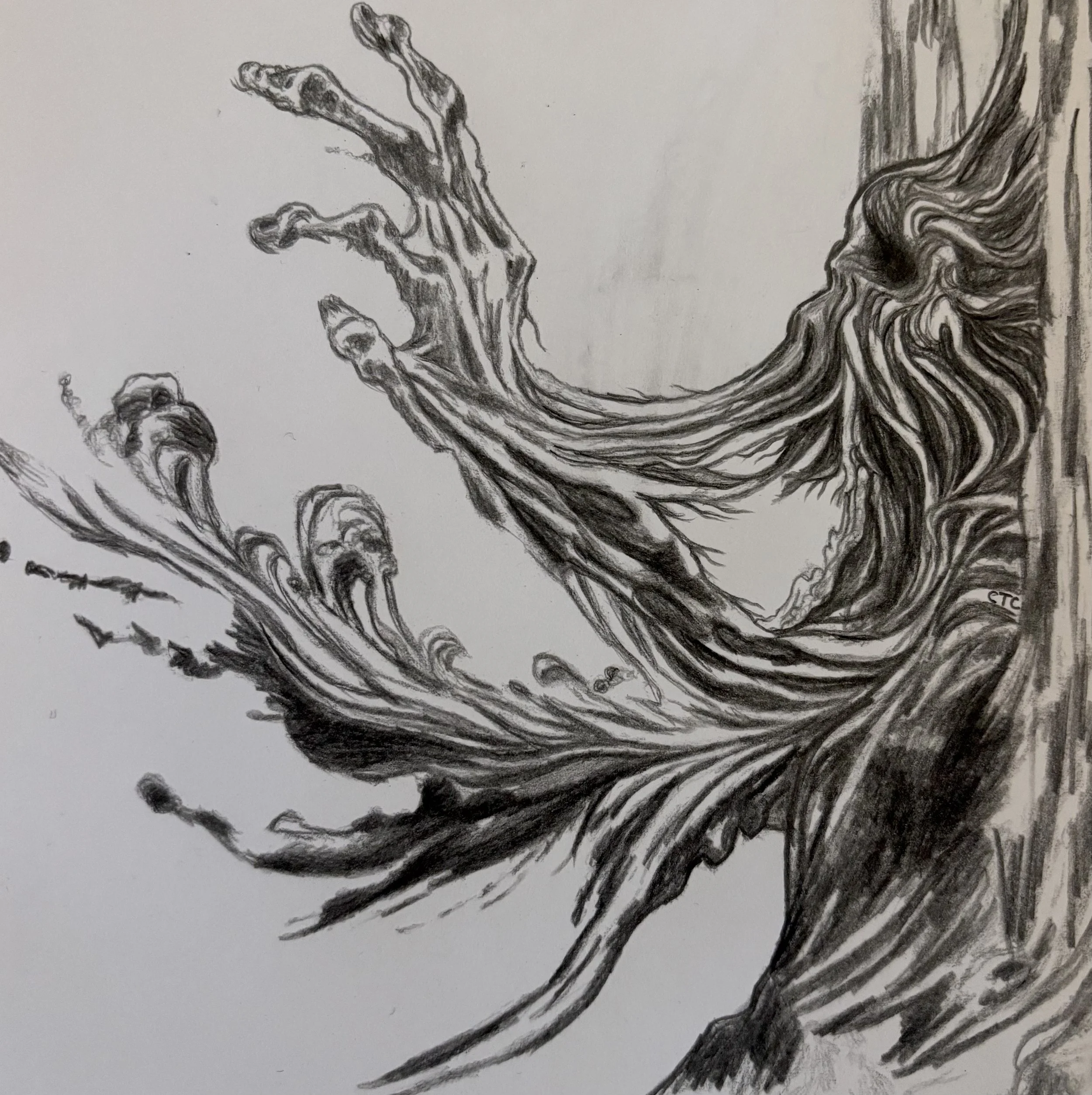

There are things in this world that listen for the new, bright sound of untrained magic and come like moths to a candle. We have long named some of them in the old lists as shadow-thing, brume-hunger, or night-gleaners, but what the boys on the cliff encountered is in an awkward, peculiar class I offer here as Shadow Feeders. They are not spirits of place in any honest sense. They are not guardians, nor are they simple malignancies. They are appetite given attention, old as the undercurrents and as small as the gap beneath a fingernail.

What they are

• Shadow Feeders are composite phenomena, part hunger, part cunning. To a scholar’s eye, they resemble a predatory pattern more than a being. In daylight, they look like a darkness that moves against the grain of light, like ink not cast but alive. Up close, they adopt textures that betray their lineage: the slick patience of eel, the slow pooling of oil, the thin, leathery reach of vine tendrils. They have no true face. Their sense is hunger; their perception is the taste of magic on the air.

Where they dwell

• They favour fissures, caverns, river mouths, the dark hollow of ship keels and the shadow beneath cliff ledges. Places where water and stone keep their breath slow and the sun struggles to lay a hand. They prefer thresholds, margins, the long seams where one element leaks into another. In old maps, they are not charted. They are noted by fishermen as long shadows that do not move like fish, by shepherds as odd hollows that smell like winter, and by a few cautious scholars who have left marks on parchment with a shaky hand.

How they feed

• Shadow Feeders hunt what sings. They are drawn to raw, newly awakened magic in the same way night flowers open to moonlight. Untrained sorcery, blood-magic stripped of ritual, sudden flares of ancestral power, these are their feasts. They do not consume flesh so much as the thread of force that makes a live thing whole. The touch is a taking of tone and momentum. Where their tendrils meet magic, there is a soft voiding, a cold that is not mere cold but the sensation of a colour being leached. In small prey, they draw sleep or listlessness. In larger or very bright targets, they will attempt to disrupt the pattern, swallowing and retaining the note for themselves.

Defences and remedies

• Some measures work, and some do not. Fire and iron are clumsy in the face of such subtle things; they flinch but are not undone. Ritual, studied and repeated, is the most reliable safeguard. A named song, sung with the skin keyed by salt and breath, will throw a Shadow Feeder back when the name is old and precise enough. Anchoring raw magic with binding charms slows the scent it gives off and makes it less appetising. The older method, and the one that saves most folk, is to teach the newly awakened to sit with their power, to feed it small offerings and ask for it in return rather than to let the power thrum open like an unclosed door. Presence, the steadying company of those who will not abandon a trembling person, forms a kind of living ward. Not everyone believes in such soft defences, but they are what the elders have returned to when bolts and blades fail.

A note on appetite and lineage

• Shadow Feeders seem to favour what is fresh. Elvish awakenings, bloodlines newly stirred after generations quiet, they shine a beacon. This suggests they are tuned not to species but to novelty and vibrancy. Where a practised mage wears a woven cloak of control, a newly risen current smells like a lamb to these things. That is why the young and untrained are particularly vulnerable.

An old fragment of a song. This fragment I found in a reed-bound scrap of a fisherwoman’s ledger in Lismere. The hand was a child’s, the ink bled with salt, and it folded into the pages of a marriage ledger as if the writer had been ashamed. I preserve it here exactly as I found it because the small cracks tell more truth than tidy copies.

“They came from the seam where the shoreline forgets its name

and drank the new bright from the mouth of the child.

We braided our hands and sang the old names,

We put our weight like stones against the wanting,

and the dark spat out its last, thin hunger and went to sleep like a tide.”

Scholar’s gloss on the song

• The poem is simple, and its simplicity is why it survives. Note the image of the shoreline as an element that loses itself. The Feeders prefer that forgetfulness. The community’s response in the song is not martial. They braid, they sing, they make themselves heavy with presence. The verbs are domestic. That choice of language tells me something important about how pre-modern folk understood these phenomena. They were not enemies to be killed but hungry moths to be dissuaded, guests at a poorly guarded table.

• The line about the child who is ‘new bright’ offers a direct analogue to Bran’s cliff moment without spoiling the account. Heroic violence is absent. Instead, we see a communal, almost liturgical defence. The song insists that naming, gathering, and weight are defensive acts in themselves. From this, I take a practical lesson: ritual without spectacle saves more lives than spectacle without ritual.

Closing field observation

• Shadow Feeders are not moral agents. They do not gloat. Their hunger is amoral and old. That does not make them less dangerous. They are complicit in myths because they make brilliant, sharp stories: a sudden fall, a child saved by a weird, unlooked-for thing, a village banding to sing at the edge of night. For those who study MirMarnia, it is worth carrying two truths at once. First, these feeders pose a clear and present danger to those with live power. Second, that they are also a lens through which our communities reveal how they care for the fragile new things among them.

If you meet one

• Make noise with names. Offer a ritual before striking. Bring company and salt. Do not assume steel will be enough. And, if you are a scholar like me, do not write their anatomy too neatly. Some things will remain dark in the fissures for a reason.

By Maelin of the Low Reach, marginalia from the fifth year of the Tideborn Catalogue