Extract from The Riverward Chronicles, Volume II

Preserved in the Hall of Drakkensund, copied from earlier manuscripts of uncertain date.

On the Discovery

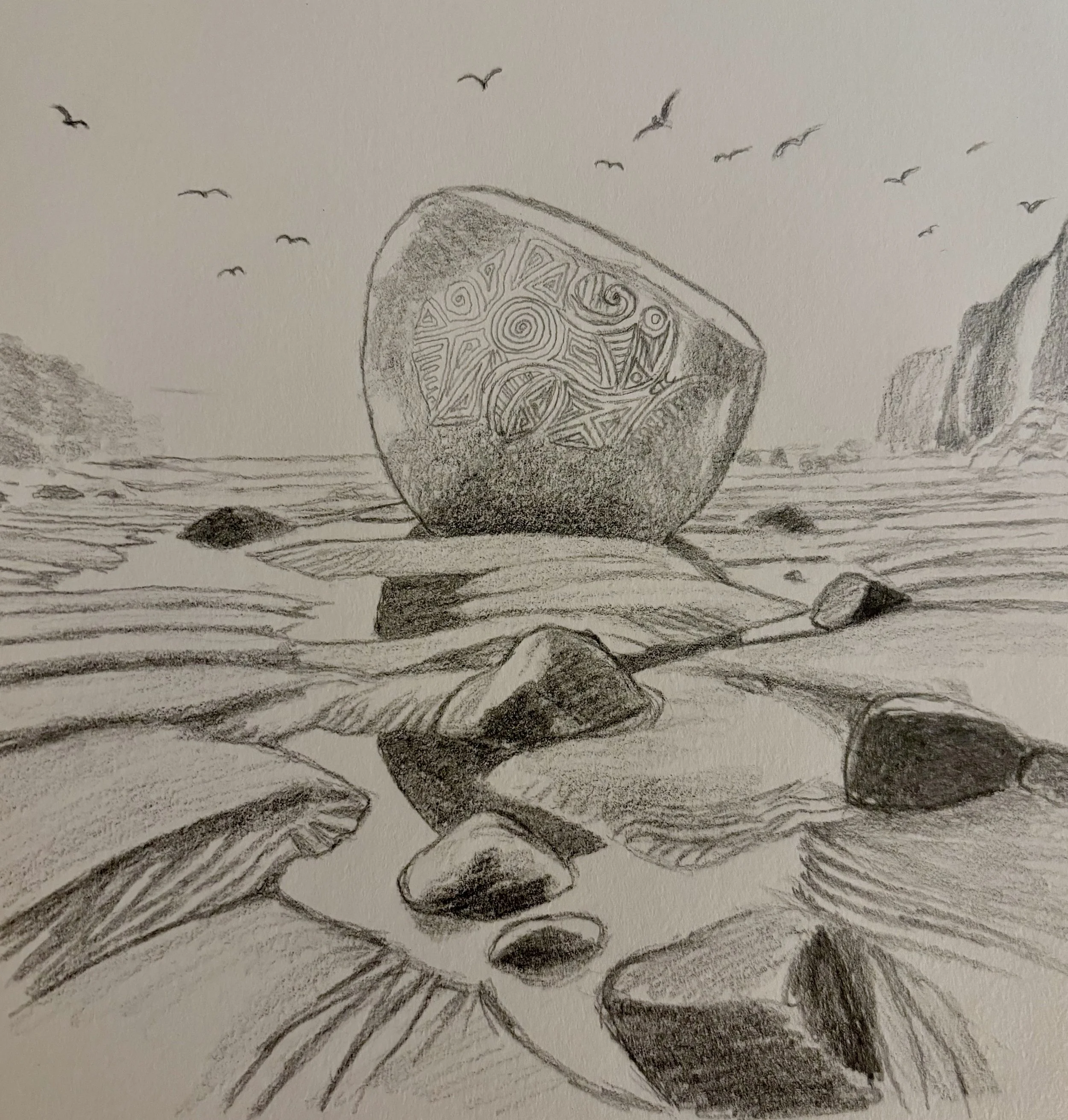

It is recorded that in the Year of the Waning Frost, the Emaris fell to an unseasonal low, bearing stones long hidden in her channel. Amongst them was a boulder of uncommon size, its face carved with words in a hand both deliberate and enduring. The stone lay amidst the cries of gulls, whose shadows wheeled across the wet sand, and the restless scuttle of crabs that gathered in the shallows. Witnesses remarked that the air itself seemed hushed, as though the river had drawn back not only her waters but her breath.

The Inscription

“Sought you on the tide, I did.

You and my mother caught in the green foam,

a tangle of death on the rocks,

and the frozen dark channel waters filling your eyes,

that stare unbroken,

but by the waving crabs that seek the juices beneath your skin,

stretched and loose,

only advertising your ripe organs,

to black‑tipped winged shriekers,

that swoop and dive,

on the gusts of the moon‑driven tide.”

Collected Interpretations

• The River Shamans: They held that the carving was no mortal lament but the Emaris herself speaking through stone. To them, the “mother” was the river, both cradle and grave, who gathers her children and releases them only when she wills.

• The Folklorists of Drakkensund: They judged it a funerary verse, perhaps carved by a survivor of shipwreck or flood. The stark images of carrion birds and crabs were not embellishment but truth, a reminder that the river grants no false comfort.

• The Language Historians of the North Bank: They observed that the rhythm of the lines echoed fragments of older tide‑chants. In ancient practice, families sought their lost upon the returning tide, believing the waters might bear loved ones back. Others sought fortune in the same rhythm, trusting the tide to deliver blessings as well as bodies. Thus, they argued the poem may hold both meanings at once: grief and hope, loss and return.

Symbolic Weight

The carving has since been taken as an emblem of the tide’s dual promise. The black‑tipped shriekers, known in common speech as gulls, are here recast as omens, their cries marking the passage between worlds. The “unbroken stare” is read as the persistence of memory, the refusal of the departed to vanish entirely.

Observations at the Site

Those who linger near the boulder report that the river’s cadence alters there. The usual rush of current deepens into a low, mournful tone, as though the Emaris herself recites the lines back to those who listen. At dusk, the shriekers’ cries sharpen, echoing the poem’s imagery with uncanny precision.

A Recorded Encounter

One villager of the lower banks, having laid bread and salt at the stone, claimed that as the tide returned, the shriekers circled lower, their wings brushing the water, while the crabs gathered in a ring about the boulder. He reported hearing the poem whispered not in his ears but within his chest, as though the river had spoken through his own breath. He would not reveal its meaning, only that he would never again walk the channel at low tide without reverence.

Later Marginalia

• “This hand is not of our age. The cuts are older than the Year of Frost, though the river kept them hidden. Perhaps the Emaris chooses when to reveal her words.” Note in the margin of a 3rd‑century copy.

• “The shriekers are but gulls. To call them omens is folly. Yet I confess their cries at dusk do unsettle the heart.” Annotation by Scholar Edran of the South Bank.

• “If the mother is the river, then who is the ‘you’? A lover? A child? Or the reader themselves, sought and judged by the tide?” Question scrawled in faded ink, author unknown.

• “Best not to linger at the stone. The last apprentice who did so was found sleepwalking into the channel.” A warning was added in red script, later by hand.